Page 118 - ShowSight - July 2019

P. 118

Form Follows Function: The Straight Column...Part 7 BY STEPHANIE HEDGEPATH continued

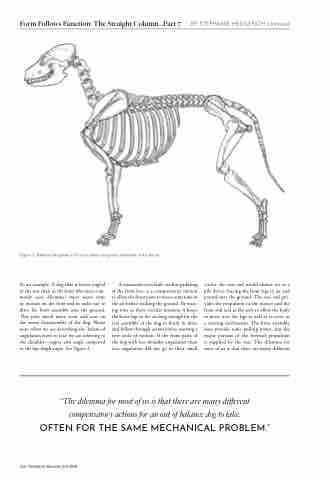

Figure 3. Balanced Angulation Front and Rear Using the Landmarks of the Bones

As an example: A dog that is better angled in the rear than in the front (the most com- monly seen dilemma) must waste time in motion on the front end in order not to drive his front assembly into the ground. This puts much more wear and tear on the entire foreassembly of the dog. Please note: when we are describing the 'balanced angulation front to rear' we are referring to the shoulder—upper arm angle compared to the hip-thigh angle. See Figure 3.

A commonly seen fault, such as paddling of the front feet, is a compensatory motion to allow the front paws to waste sometime in the air before striking the ground. By wast- ing time in these circular motions, it keeps the front legs in the air long enough for the rear assembly of the dog to finish its drive and follow-through action before starting a new cycle of motion. If the front paws of the dog with less shoulder angulation than rear angulation did not go in these small

circles, the rear end would almost act as a pile driver, forcing the front legs to jar and pound onto the ground. The rear end pro- vides the propulsion (is the motor) and the front end acts as the pole to allow the body to move over the legs as well as to serve as a steering mechanism. The front assembly does provide some pulling power, but the major portion of the forward propulsion is supplied by the rear. The dilemma for most of us is that there are many different

“The dilemma for most of us is that there are many different compensatory actions for an out of balance dog to take, OFTEN FOR THE SAME MECHANICAL PROBLEM.”

112 • ShowSight Magazine, July 2019